Offshore Exposure Keeps Thailand from Easing

Trade Surplus has historically strengthened the THB, but what happens when the exporters' earnings don't return?

The Bank of Thailand (BOT) has recently taken a hawkish stance. Deputy Governor Piti Disyatat said there is little “room” left for easing, and outgoing Governor Sethaput Suthiwartnarueput noted that policy “ammunition” is limited. Despite weak growth and low inflation, the BOT continues to hold rates. Why?

Domestic conditions may justify easing, but structural FX imbalances and the global backdrop leave the BOT constrained. A rate cut could fuel capital outflows, deepen the positive CIP basis, and unsettle the baht, offsetting any intended stimulus.

This article will first articulate the recent BOT cutting cycle and the conditions in which the BOT tends to ease monetary policy. Next, how Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs) and exporters interact with the financial system architecture is considered. And lastly, the THB market is analysed through the lens of the US-China trade war.

Bank of Thailand’s Rate Cut Cycle

The BOT finally began its cutting cycle in Oct 24 after heavy political pressure. It appears most comfortable easing when the THB is strong or strengthening, as seen with the 16 Oct 24, 25 Feb 24, and 30 Apr 25 cuts. A weak THB squeezes margins in an import-dependent economy, which likely explains the skips in Nov 24, Dec 24, and Mar 25.

Debt levels are still a concern. Households remain overleveraged, a point discussed in “Thailand’s Household Debt Problem.” BOT’s restructuring and forgiveness efforts have slowed debt growth, but deleveraging has not materialised. Still, that was enough to give the BOT room to cut late last year.

Domestic firms continue to struggle. Exporters have seen shipments and inventories decline since May 24. This persistent weakness fuels the government’s ongoing calls for rate cuts.

Thailand is also hovering near deflation. Domestic demand remains weak, and households are under pressure. The digital wallet scheme pushed by PM Paetongtarn has not been enough to lift consumption.

In most countries, poor growth and low inflation would justify easing. But in Thailand, high debt and structurally low neutral rates complicate the picture. With policy rates below 2%, capital continues to flow out. Onshore firms chase better yields abroad, and offshore firms avoid holding funds in a low-return, volatile currency.

Financial Infrastructure Incentivises Fund Offshoring

Thailand’s open and ageing economy breeds an interesting dynamic.

Openness gave rise to major export sectors like Semicon and Autos. Exporters must manage their foreign earnings to balance profit with FX risk.

Ageing pushed the growth of large Pension, Life Insurance, and Mutual Funds, collectively referred to as NBFIs. But Thailand’s capital market is too shallow to absorb their assets, prompting significant offshore investment by domestic institutions.

Exporters

Like many exporting nations, Thailand continually post positive trade surpluses as it adopts the export-led development model that the Four Asian Tigers innovated. These outflows represent significant FX risk. Exporters’ earnings are in USD, but their liabilities and labour costs are denominated in THB. A tolerable circumstance if Thai exporters hedge their earnings.

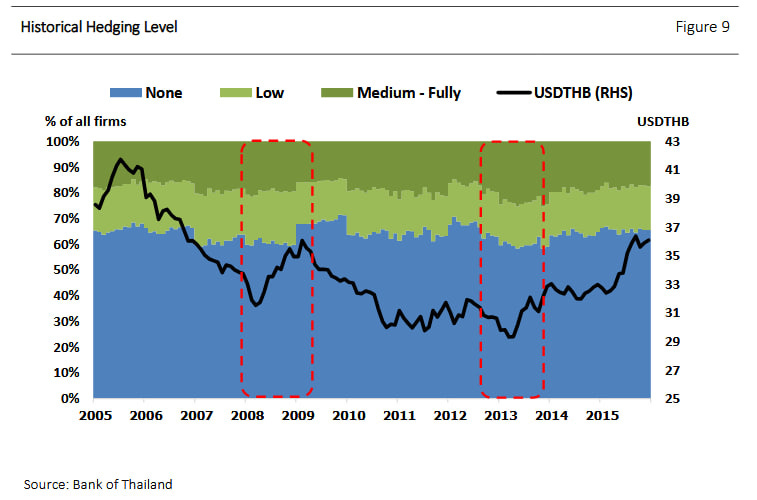

However, exporters often choose to go into transactions unhedged, with only ~20% of firms fully hedging and another 20% partially hedging. The rest opt to face FX risks.

Willingness to be exposed to FX risks stems from the “auto-correction” of returns in USD. In a risk-off environment, equity tend to sell off, however, this is cushioned by the strengthening USD. On the other hand, risk-on sentiment tends to lead to significant capital appreciation and strong returns on exporters’ offshore USD holdings.

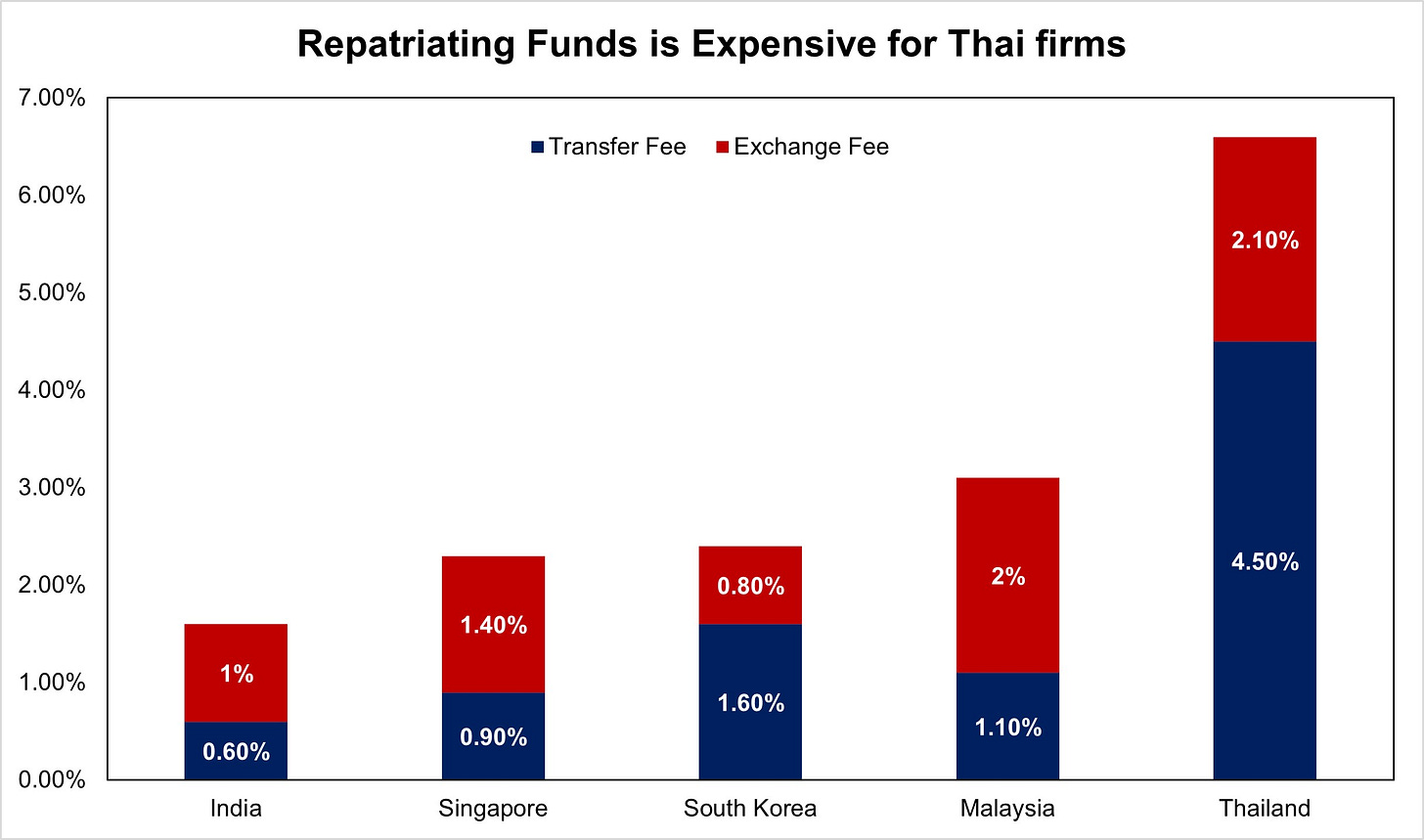

Furthermore, Thai firms face significant costs to even onshore their funds. The concentrated nature of the Thai banks, relatively tight capital controls and thin THB liquidity are key contributors to the expensive transaction fees. It is not cost-effective to onshore their funds if >5% of their earnings are used to pay intermediaries.

The high structural costs lead to exporters mandating that their clients directly pay their onshore account (Red in the figure above) or they keep their earnings offshore (Blue in the figure above). This means that there is a significant amount of Thai earnings that are never repatriated back home. Exporters use their offshore holdings to net off import costs and invest the rest. Staying unhedged also allows them to double-dip, enjoying capital gains and FX gains when the THB is weak.

Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI)

As Thai society ages, workers raise precautionary savings to secure retirement. They can no longer rely on their children for support, especially as the dependency ratio rises.

Retirement savings are managed by Life Insurance, Pension, and Mutual Funds (NBFIs). These institutions face long-duration liabilities and must invest in long-duration assets. But the domestic market is too shallow where large moves by NBFIs distort prices. Furthermore, local bonds offer low yields compared to global markets.

As a result, NBFIs have steadily built offshore positions. Their external asset holdings grew from USD40mn in 2001 to USD113bn in 2023.

The initial accumulation was in offshore bonds, but NBFIs quickly raised their exposure to equities post-2008. hey are barred from holding mortgage-backed securities and similar assets, so their debt holdings are concentrated in investment-grade bonds and US Treasuries. This increases Thai exposure to the gyrations in the US Treasury market and, more importantly for us, the FX market.

Thai regulators desire a high FX hedging ratio to reduce FX risks in NBFIs. Unlike exporters, NBFIs are often well protected against FX risk.

The Office of Insurance Commission only allows Lifers to have a limited ratio of unhedged holdings to solvency capital.

The Security and Exchange Commission have hedging requirements that have led to equity funds averaging a 66% hedge ratio, and 96% for fixed income funds.

This is encouraged by the BOT, which has eased FX transaction regulations to allow non-banks to provide FX services.

BOT has also expanded the hedging instruments offered in 2020.

Thailand’s strong net IIP suggests heavy hedging demand from NBFIs. Telok Ayer estimates that around USD40bn in Thai external assets require monthly hedging.

Since exporters don’t repatriate earnings, the THB market remains thin. This limits hedging capacity onshore, pushing NBFIs to rely on offshore markets. BOT estimates that 61% of all THB transactions and hedges now occur offshore.

In short, NBFIs have significant foreign FX-denominated assets, but their liabilities (payouts) are locally denominated. The need to fully hedge positions in a thin FX market forces transactions offshore. As a result, the THB is exceptionally sensitive to global market movements.

Putting it together

The Thai market structure forces exporters and NBFIs alike to hunt for returns offshore and disincentivises the onshoring of funds. Asymmetries in FX hedging regulations have placed the burden of market adjustment on NBFIs, complicating the BoT’s policy calculus.

Exporters remain largely unhedged and keep earnings offshore to avoid FX risks. If the BOT cuts rates aggressively, the THB will face sharp depreciation. Lower yields reduce the appeal of THB assets and increase the opportunity cost of holding foreign assets. This drives capital outflows, reducing foreign exchange supply onshore and pushing hedging costs higher.

NBFIs, fully hedged, bear rising hedging costs. Their demand for USD and USDTHB forwards grows as they seek higher yields abroad. A BOT rate cut would increase this demand, pushing USDTHB and forward prices up. This trend is evident in the strong positive USDTHB forward basis since Jan 22.

Foreign investors face limits on their Non-Resident Baht Accounts and cannot supply enough USD or forwards to balance the market. This raises the risk of a sharp positive basis. NBFIs would likely absorb these costs, increasing the risk of financial instability.

Amplification of the US-China Trade War

BOT’s dilemma is compounded by the re-pricing of global trade risk. As US-China tariffs unwind and the USD strengthens, the incentive for Thai exporters to hold earnings offshore increases, amplifying THB depreciation pressures and deteriorating the hedging backdrop for NBFIs.

The pause in US-China tariffs has triggered a wave of risk-on sentiment, but the implications for Thailand are far from reassuring.

Markets are now discounting China’s tail risks and discounting US recession expectations. As a result, the USD is strengthening and Treasury yields are rising. Even without a rate cut from the BOT, this macro backdrop is already pushing USDTHB higher and exposing the weak spots in Thailand’s FX structure.

The BOT is in a dilemma. Cutting rates now would accelerate THB depreciation, but standing pat risks falling behind the global easing cycle. From this perspective, USD strength is not just a byproduct of sentiments, but also a catalyst for trade and portfolio imbalances.

At the same time, FX policy is being politicised again. Reports from South Korea’s 5 May trade talks suggest the US may be pressuring EM Asia to release their hold on domestic currencies. US officials have since denied any discussion of FX policies, but markets are nervously watching closely for signs of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” in the making. The BOT now has to walk a fine line. Too much THB volatility risks triggering US scrutiny, but too little action will add to capital outflows and strain hedging markets.

Thailand have limited options in their response to the weakening THB. Malaysia, for instance, can call on Petronas to repatriate earnings. Thailand cannot. Its exporters are mostly private, and its capital markets remain relatively open. A coordinated "Great Repatriation" is not on the table.

Additional headwinds are likely as the US-China tariff pause expires on 10 Aug 25, while the reciprocal pause on Thai goods ends earlier on 9 Jul 25. If these deadlines hold, markets may begin to price in renewed trade friction, putting upward pressure on USDTHB. In the lead-up to this window, the THB is likely to remain under pressure and struggle to stabilise.

As USDTHB rises, unhedged exporters have even less reason to bring earnings home. This further tightens onshore USD liquidity, raises hedging demand from institutional investors, and pushes the market forward much higher than its fair value. Without a concrete, long-term US-China tariff deal, the pause has the potential to inject more (not less) volatility into the USDTHB market.

A disconnect between markets and the real economy

While optimism abounds in the financial markets, the real economy adapts at a much slower pace. The rising USDTHB may, in theory, lead to more price-competitive exports. However, since supply chain deals are often multi-year affairs, this means that bouts of THB weakness are an insufficient growth boosting mechanism. The underlying problem is that US tariffs are here to stay, and the floor appears to be 10%. The UK-US deal and the US-China pause show us that it will be difficult to regain the era of low trade barriers.

Thailand have been struggling with a productivity and education problem. While their exporting industries are well developed, stagnating productivity gains in Thailand will slowly erode their competitive advantage. Competition from Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam developing their semicon and auto assembly ecosystems will quicken the erosion. Weak THB, trade deals, and BOT cuts are no panacea for these structural issues.

Conclusion

The BOT is in a bind. Thailand’s large external asset holdings complicate the transmission of monetary policy. From this point forward, further policy rate cuts are unlikely to meaningfully boost private investment or consumption. Instead, if the BOT quickens the rate cut cycle, it risks triggering financial strain for NBFIs and encouraging more capital outflows from exporters, which could cause the policy to backfire. While the BOT, in general, prefers a weakening THB, a premature rate cut would likely cause this depreciation to be disorderly and cause market turmoil.

Current Governor Sethaput’s 5-year term ends on 30 Sep 25, which means he will only lead the 25 Jun and 13 Aug monetary policy committee. By 2 Jul, the BOT should announce the front-runners for Sethaput’s role. I foresee strong political pressure in the coming months to cut rates, especially since the outgoing Sethaput is a prominent defender of BOT independence.

In all, BOT is likely keeping rates stable in the near future. I believe that the BOT should not tweak monetary policy for the rest of the year. However, with growth concerns mounting, the political pressure to act will be insurmountable and may result in two 25bps cuts at the last 2 meetings of the year.