Now more than ever, Nusantara should stick together

Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia benefits from closer ties amidst an uncertain world

During the Peloponnesian War, Athens landed on Melos, a Spartan ally, and demanded submission. The Melians declared neutrality, but in response, the Athenians merely quipped: “The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must.” The democratic Athenians then massacred the men and sold the Melian women and children into slavery.

Whether or not the Melian Dialogue truly happened, it captures an enduring truth: small states must survive by strategy, not sentiment. For decades, intergovernmental organisations and American power provided cover. But in a Trumpian world order, the age of “might makes right” returns, particularly troubling for the small, trade-dependent democracies of the Malay Archipelago.

The Malay world of Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore has had a civilizational identity rooted in trade and cooperation. These countries make up a region often called “Nusantara”, which we will use in this article to refer to the tri-party bloc. Nusantara have long stood as a beacon of success in emerging markets. But as multilateralism fades and tariffs rise, their fate depends not on external guarantees but internal alignment. This article argues that a flexible, event-driven alliance between these three states is both viable and necessary.

Why didn’t ASEAN negotiate together?

ASEAN, designed to be the platform for regional unity, has proven to be toothless during this trade crisis. Its members have pursued individual deals with US officials, abandoning the idea of a collective negotiation strategy.

Even recent gestures, like Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s vague call for “mutual understanding within ASEAN,” reflect more aspiration than action. In practice, ASEAN has long been fractured along lines of self-interest.

The clearest problem is trade policy. Reciprocal tariffs from the US range from 10% to 46% across ASEAN. Sector-specific variations, like exemptions for semiconductors but not automobiles, further splinter member interests.

This divergence is evident in effective tariff exposure. After accounting for sectoral exemptions, Malaysia would have faced only 18.8%, while Vietnam and Thailand were looking at over 41% and 32%, respectively.

Furthermore, Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia all target the same sectors: electronics, automotive, and data centres. In this context, getting a better bilateral deal than your neighbour becomes a competitive advantage.

It is important to note that announcing a deal with the US too early can be disadvantageous. Competing economies may examine the initial agreement for precedent and then use it as a blueprint to gain more favourable terms for themselves.

These dynamics have strategic implications. Low-tariff countries can afford brinkmanship. High-tariff ones feel pressured to settle early, even if that means setting precedents others will exploit. This creates a prisoner’s dilemma: no one wants to be first to concede, but each country is tempted to act alone to secure an edge.

Even a united ASEAN front might collapse under the weight of intra-bloc cheating. Governments under competitive pressure would be incentivised to undercut the collective position behind closed doors.

Consensus, a foundational principle of the ASEAN bloc, becomes its Achilles’ heel. ASEAN, in its current form, offers no mechanism to coordinate this behaviour. Therefore, the equilibrium settles into the current state, individual economies negotiate with the US alone and struggle to come up with sufficiently attractive terms.

But Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore should negotiate together

Unlike their ASEAN peers, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore have a foundation for strategic cooperation. Their economies are more complementary than competitive. For example:

Malaysia and Singapore export refined petroleum, Indonesia’s largest import.

Indonesia exports coal and copper, critical industrial inputs for Malaysia’s industrial sector

Malaysia and Singapore has deeply integrated supply chains, particularly in the electronics sector.

Singapore is a major FDI source for both Malaysia and Indonesia.

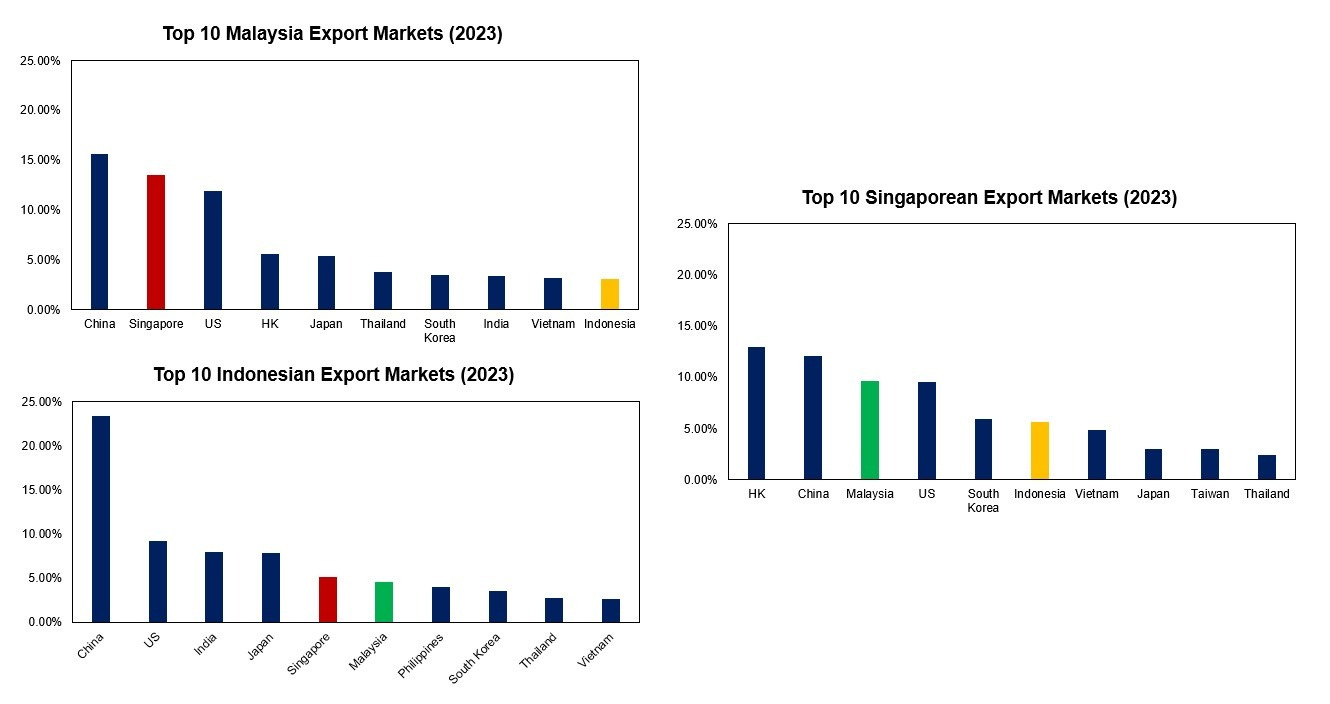

However, the linkages are not fully mature, while the three nations are all firmly within the top 10 export partners of each other, they still largely trade with global partners. While this might indicate that the three economies are open and allow for the free movement of goods, it might also point to the underdevelopment of regional trade.

In a volatile geopolitical environment, relying heavily on exports to large, great powers is a risky proposition. As we saw from the recent US tariff on Southeast Asian solar panels, having strong linkages with China may put economies in the crosshairs of the US.

Facing the same geopolitical calculus

What sets Nusantara apart is not just economic structure but geopolitical symmetry. All three states adopt the ideology of bebas aktif, or "independent and active", which seeks balance rather than partisan alignment.

Strategically, Nusantara controls the Strait of Malacca, giving it outsized leverage in a US-China confrontation. While other ASEAN states like the Philippines lean strongly towards the US and Cambodia leans towards China, the Nusantara states share a middle path. This makes consensus-building far easier. Moreover, they are less entangled in divisive issues like the South China Sea or the Myanmar crisis. This insulation enhances their capacity for independent action.

Getting ready for a turbulent world

We are entering a world that resembles the ancient mandala system more than the post-Cold War unipolar moment. States gravitate toward power centres as circumstances dictate. In this world, power and agility yield a premium.

A flexible Nusantara alliance can operate like the Quad or G20, not a rigid bloc, but a platform that increases in activity during turmoil and becomes less active in times of stability. This model reflects how real diplomacy often works: ad hoc, interest-based, and situationally responsive.

For tariff negotiations, Nusantara could present a united front, offering concessions as a bloc. One option might be a Malacca Straits Maritime Authority, granting the US preferential access to logistics infrastructure and targeted tax waivers. This could pave the way for arrangements like a “China Alternative Partnership Clause,” where US firms relocating supply chains to the region receive tax holidays, expedited customs, and digital fast lane clearance. This reduces reliance on China while securing access to regional raw materials and lower-value production.

Trump’s return and his preference for strength-based bargaining only heighten the need for this structure. Consider how China secured reciprocal tariff cuts from the US, while the UK, despite political goodwill, received no such benefit. Size and leverage matter.

Turbulence as an opportunity

Recent appreciation in AsiaFX due to a weaker USD has created an interesting dynamic in EM Asia. Trade competitiveness can be quickly improved in the short term through 1) unilaterally weakening your domestic FX and 2) striking a favourable trade deal with the US.

Since ASEAN economies are mostly competing against each other, there is a strong incentive for a country to gain an advantage to increase investor interest. The first economy to quicken its cut cycle will likely experience a great re-rating of its domestic assets. Enabled by low inflation in the region, most central banks are free to ease monetary policy in the next few quarters.

The risk, of course, is the uncertainty in the market. Cutting too deeply or too early means depleting policy space for central banks to react to the reignition of trade tensions.

An alternative, longer-term response to raising competitiveness is to deepen integration between Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore. As mentioned earlier, the 3 economies are remarkably complementary. The gradual lowering of barriers alongside standardising regulations would go a long way in developing regional supply chains. Some of the work has already been done via the Singapore-Johor Special Economic Zone.

The key here is to view the recent threats to trade as an opportunity for alignment and cooperation. As the other emerging markets look to offer increasingly better deals or potentially deepen their cut cycle, Nusantara may find a middle path. Choosing integration and raising economic productivity to ensure long-term growth rather than short-term competitiveness.

Internal Political Constraints

The framework and underlying mechanism do exist for this Nusantara collective to manifest. But it all depends on the domestic political climate. Singapore and Malaysia’s current administrations are remarkably open to cooperation and integration. However, as we have seen from the High-Speed Railway, political volatility is an ever-present concern in international pacts.

Anwar’s party, the PKR, have had some internal turmoil where two senior leaders left after losing an internal party election. Meanwhile, a top technocrat from the PKR’s coalition partner has resigned and is rumoured to be joining the PKR. These moves will weaken the internal leadership structure of the PKR and possible shake the foundation of the ruling coalition’s unity.

Indonesia’s Prabowo has a different problem. Prabowo’s foreign policy ambitions seem to be much bigger than the region. He joined the BRICS alliance and has begun the process to join the OECD. He views Indonesia as a player on the global stage, and he is probably justified in this view.

Indonesia is the nation with the largest Muslim population and has a vast reserve of copper, bauxite and nickel, key industrial inputs. Indonesia has some potential to be one of the leaders of the Muslim world and grow to be the key supplier of crucial metals. As such, Indonesia gains from joining a Singapore-Malaysia pact is minimal, compared to the gains that Singapore and Malaysia might realise. While this is true, Indonesia lacks the diplomatic reputation and agility that Singapore and Malaysia have. Furthermore, to realise the potential as a world leader in resource production, greater FDI inflows are needed, and Singapore, as a financial hub, is crucial.

Conclusion

The Melian lesson is that power protects. But in a fragmented world, power can come from aggregation, not just scale. If Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore act in concert, tactically, they may not match the strength of great powers, but they will not be weak.

In this new age of geopolitics, even small alliances can cast long shadows. Especially when forged by those who understand that the world is no longer ruled by law, but by leverage. Supply chain integration and deeper cooperation offer the only viable response that leverages policy reaction to the current turmoil as a trampoline rather than a safety net.